Not Too Young

Reading Time: 8 minutes

By Laila Rousari

Breast cancer at age 28? It’s as bad as you would imagine. I’d like to share the unique challenges that come with breast cancer diagnosis at a young age.

Too Young for Breast Cancer

Most people thought I was too young to have breast cancer. They didn’t take my lump seriously. Their response made me feel crazy; I thought it was breast cancer and they didn’t.

Two things that made my diagnosis worse: having a PhD in cancer research and knowing the story of my aunt’s diagnosis at age 17. Even my family thought I was a bit crazy, but I could not shake my unsettled feeling. I had to keep pushing, harder than I expected I would have to. I talked to as many medical professionals as I could that would listen to my story. It takes a lot of courage to stand up to medical professionals. Even with my background, I often go into a doctor’s office with a list of ten questions and ask the three easiest and tell myself I’ll save the rest for later, which never happens.This happens especially when they’re deeply personal or related to reproductive health.

The Stakes Were High

The consequences were too scary. It was so unlikely to be breast cancer at my age that even the genetic counselors thought my family history wasn’t suspicious enough. It’s scary and hard to advocate for yourself and not all medical professionals make it easy to speak up. It turns out, a year and a half later from being diagnosed with stage 2 breast cancer, I’m definitely not too young to have breast cancer and I don’t have any known genetic mutations. So there, that’s the first thing about being young with breast cancer. Diagnosis can be a challenge. And the scariest part is, I’ve heard so many other young women tell the exact same story as I mine. I was fortunate to have a background in cancer research. My background helped me fight to get answers, but not everyone has that. And really, no one should have to.

What happens next?

It’s the time to make life-altering decisions. The clock is ticking and you have to make these decisions in a matter of weeks.

Surgery or chemo first?

This was a huge one for me. This decision would directly impact another big decision: children. If I chose to do surgery first, I’d be able to squeeze in an egg harvest before starting chemo, allowing me to preserve my fertility. If I chose chemo first, we could monitor my tumor and see how responsive my tumor was to the chemo and make changes if necessary. So what this came down to was one key question – do you want to have kids? I wasn’t married; divorced actually. I was dating someone but we were together for less than a year.

“Hey guy who I’ve dated 10 months, assuming we get married and have kids, how many do you think you’d want? Ok great, now on to deciding chemo regimens.”

I always assumed I’d have kids but I’ve always been career oriented so I hadn’t spent much time thinking about it yet. Most women with breast cancer have already had their kids. Yet here I was left to make this life altering decision in a moments notice. “Hey guy who I’ve dated 10 months, assuming we get married and have kids, how many do you think you’d want? Ok great, now on to deciding chemo regimens.” That’s pretty much how it goes.

And to top it off, since I’m a scientist, I felt that I had to read every study published in the last 10 years about treatment of breast cancer to feel confident in my decision. Again, back to feeling like I’m annoying my doctors by asking them questions, when all I want to do is make the best, informed decision I can.

The Impact of Treatment

We’ve talked about fertility, relationships, and making totally overwhelming, life-altering decisions in a matter of weeks, what else do young women with breast cancer face? Well, there’s the impact treatment makes on our careers.

We’ve talked about fertility, relationships, and making totally overwhelming, life-altering decisions in a matter of weeks, what else do young women with breast cancer face? Well, there’s the impact treatment makes on our careers.

We don’t have long-established careers. It’s quite the opposite, actually. I spent the first half of my twenties working towards my PhD. At the time, I was 1.5 years into my first job. I had landed my dream job, hired my first employee, and then I realized I would have to miss significant chunks of time at work.

I had a crucial assignment that I couldn’t make progress on. The deadlines around it weren’t going to change but I couldn’t be there. So all throughout treatment, I worked hard to maintain as much of an involvement in my job as I could, often taking the first or last appointments of the day and spending all of the time in between at work.

Another Tough Decision

It was not that my job didn’t support my leave or my manager wouldn’t let me take the time. It was that I didn’t want cancer to get in the way of my blossoming career. Cancer was already taking my breasts, my hair, my fertility, my strength; I wasn’t going to let it take something I worked so long and hard for.

Working throughout was exhausting, both mentally and physically. It drained me, but it was the one thing that kept my life feeling somewhat normal. I was happy when I was at work and could spend a few minutes forgetting about ‘cancer me.’ Was it worth it? It absolutely was. I earned a promotion that year. We made so much progress on the project for which I am so proud. Was it the hardest thing I’ve ever done? Absolutely.

Survivorship Sets In

I made the tough decisions. I maintained my life and career throughout treatment. How does it feel? Mixed, very mixed. I’m relieved to be cancer free, but it came with a price.

I made the tough decisions. I maintained my life and career throughout treatment. How does it feel? Mixed, very mixed. I’m relieved to be cancer free, but it came with a price.

Imagine this: You are a young, single woman with a rocking body from running marathons. Your hair is thick and long and your brows are fluffy (the kind of fluffy people pay lots of money to get). Over the course of treatment, you lose all of your hair, your muscle tone, and your bone density (among many other things). Essentially, you aged 30 years in the span of 1 year.

I was okay with losing my breasts. They actually offered to just take one and I told them to take both, without any hesitation. I didn’t want one real boob and a higher chance of recurrence. But when they told me I had to lose my hair, I couldn’t cope. I always had long hair and, like many women, I felt it was a part of my identity. I knew if I lost my hair, I’d look like a cancer patient and at the time, that seemed like the worst punishment of all. Take my breasts, my energy, my fertility, but please don’t take my looks.

I know that sounds vain, but I was 28! What 28-year-old doesn’t care how they look? The idea of wearing scarves or wigs was mortifying. What would people think?

Enter: G.I. Jane

One really striking memory related to my hair loss journey was with my dad. I had been feeling pretty bold as I prepared for hair loss. So I buzzed one side of my head, then my whole head. I felt a bit like G.I. Jane.

One really striking memory related to my hair loss journey was with my dad. I had been feeling pretty bold as I prepared for hair loss. So I buzzed one side of my head, then my whole head. I felt a bit like G.I. Jane.

Then my hair started to fall out so we decided to shave it clean. My dad did it and we cried together the entire time he was doing it. I was completely torn apart inside when I looked in the mirror. It was the first time I didn’t recognize myself. It felt like an out of body experience, like someone else was looking back at me.

I buzzed one side of my head, then my whole head. I felt a bit like G.I. Jane.

My clothes stopped fitting well. A skeleton of me was there, not me. Because of that I stopped really looking at myself at all. I tied scarves, but I felt it was obvious I was bald under them. My face was puffy and my nails fell off. I felt hideous. I didn’t even have the energy to try to look better.

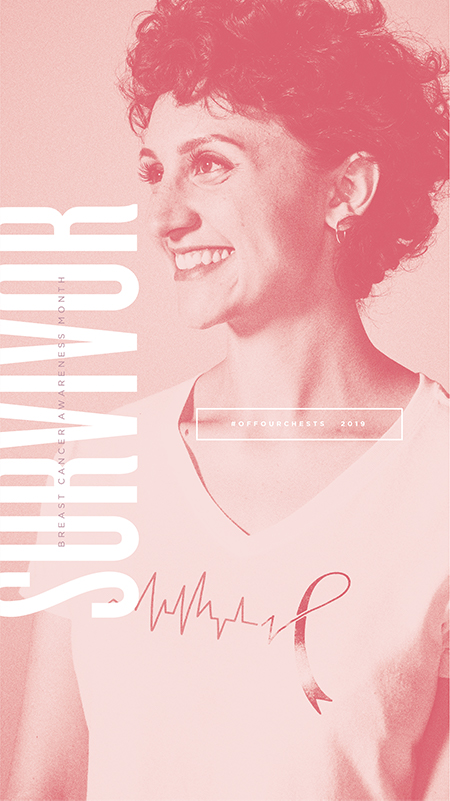

When I did try, I was even more disappointed. I still felt ugly. It wasn’t until I started coming across other women with breast cancer online who were rocking bald looks that this feeling of not wanting to look like a cancer patient changed.

I couldn’t change my circumstances, but I could change my attitude and approach. Being bald could feel empowering.

The Isolation of Waiting Rooms

What’s the hardest thing I have to deal with as a young cancer patient? Isolation. This becomes obvious in waiting rooms. As a cancer patient, you practically live in waiting rooms as I’m pretty sure you spend more time in them than at home, and your companions are all at least 30 years your senior. People look at you strangely and assume you’re the daughter or granddaughter. That is, until you lose your hair and then you get even more looks.

I noticed the way breast cancer was portrayed. Breast cancer is women in pink in their 60s doing walks, smiling and laughing with their friends. I was so angry at this stereotype because first of all, it’s not happy or fun by any stretch of the imagination. And we aren’t all 60. That’s what I noticed while sitting in those waiting rooms and that’s all I knew during my diagnosis and early treatment.

Breast cancer is women in pink in their 60s doing walks, smiling and laughing with their friends.

You feel totally alone. You feel totally isolated. I was mad at the world and everyone that was healthy. Yes, that sounds totally irrational, but it’s how I felt. I desperately needed community. I desperately needed to know if there were any other young women dealing with all of these losses that could relate to me.

Community Lifts You Up

One day at the cancer center I was waiting in line to check in for an appointment. There was another young woman in front of me in line. It was like I saw a celebrity; excited and nervous, yet desperate to meet her.

I watched for a few minutes, confirming she was the patient, not the daughter or granddaughter. I noticed her looking at me, too. She actually ended up speaking to me first, and it was like we were immediate friends, asking each other questions about treatment plans and reconstruction types. We parted ways and I so regretted not finding a way to connect with her that I ran back over to her and asked for her number. There are so few of us.

Not long after, I found The Breasties. In this community, we can be ourselves. We can be young and happy and scared and devastated and hopeful and strong and loved and weak. I have so much life I want to live after cancer. My dreams are enormous and I don’t know that I would have had the strength to pursue them out without my community, without The Breasties.

Visit here to wear your support for Kara and The Breasties. 20% of the proceeds will be donated to support their mission.